Teachers

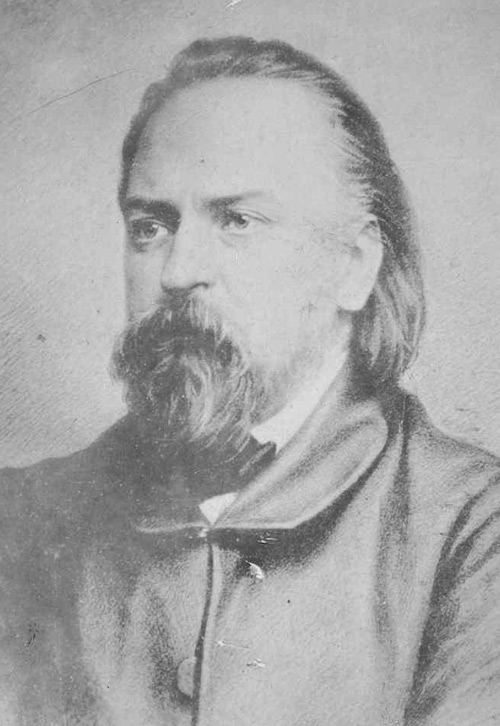

Alexander Herzen

In 1847, Herzen, a Muscovite born in 1812, left his fatherland under the control of the tyrant Nicholas is to devote his life elsewhere in Europe to what he saw as his mission in life: battling for freedom and the right of every individual to lead a humane existence. But Herzen was shocked by the Europe he found. In April 1850, in a hotel room in Paris, he wrote: ‘The visible, old, official Europe is not sleeping — it is dying!’

Internally decayed, morally corrupt and only kept in place by the authority of violence — such is Herzenʼs diagnosis of Europeʼs established powers. He sympathized with those who preached revolution but he feared the consequences of their ideological abstractions. ʻWhy is belief in a heavenly paradise foolish and belief in earthly utopia not foolish?ʼ is a question he put to his friends. Because the only thing that man has, that man needs to have, is the freedom to live his life and to give it meaning himself.

‘When anti-materialism and monarchic principles prevail instead of liberty, will you then show us a place where not only will we be left alone but also where they will not hang us, burn us or quarter us, as is now happening to some extent in Rome, Milan, in France and Russia.’

Where there is no freedom, culture cannot exist, but where culture is banned all freedom is meaningless and the rest is just arbitrary and trivial. The freedom that Herzen wanted to defend with his heart and soul was the freedom that can turn individuals into characters, that allows people to cultivate their soul and be an example of human dignity. It is for this freedom that he begins The Free Russian Press in London and establishes the magazine The Bell. He formulates the editorial aim of this magazine as:

‘Everywhere, in everything and always to be on the side of freedom, against injustice, on the side of knowledge, against superstition and fanaticism, on the side of people growing to full stature, against reactionary governments — those are our goals.’

Recommended

Alexander Herzen, My Past and Thoughts, 1852.