Literature

Hans Fallada

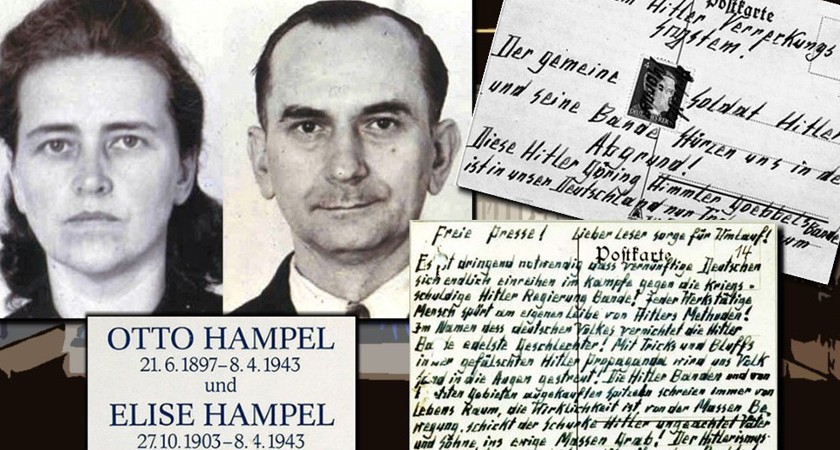

In his gripping novel Alone in Berlin, Hans Fallada tells the true story of two simple-hearted people from the German working classes, who decide to resist Hitler’s regime.

Otto and Anna Quangeln are true supporters of the Führer, until their only child is killed at the frontline in 1940. The condolence letter proclaims that their son died a ‘hero’s death for his Führer and his people’ – but Otto and Anna know this is a lie. The boy did not want to fight, he was against war. The parents are convinced that Hitler murdered their only child and decide to join the resistance. They don’t just want to resist the Führer, but also a society in which you can no longer think for yourself and always have to do what you are told. They decide to distribute cards all over Berlin. The first card shows: ‘Mother, the Führer has murdered my son.’ They aim to set their fellow citizens thinking. They hope that their peers will overcome their fears and become aware that Hitler’s regime is murderous, even that those who do not resist are accessories to the criminal regime.

But, it turns out that people are afraid and hand in the cards to the Gestapo. Eventually, the parents are arrested and know they won’t survive the trial. In prison, Otto is put in a cell with Dr. Reinhardt, a conductor who was courageous enough to warn people against the regime. Otto, an ordinary craftsman, regards the conductor with much scepticism and says: ‘Being a composer, what’s the point? I’m a cabinet maker, my work lasts for a hundred years. But music, well, when it stops there’s nothing left of your work.’ The composer replies: ‘And yet there is, my good fellow. The happiness inside that people experience when they hear good music remains.’

At a certain point a petty thief joins them in the cell and the dirty little rat steals their bread. When the composer responds to this with leniency, Otto gets angry: ‘You are too weak. We have to put this scumbag back in his place.’ But the composer replies: ‘Should we become just like the others then? They think that they can change our minds by hitting us. But we don’t believe in the supremacy of violence. We believe in goodness, in love, in justice.’

When Otto begins to doubt the purpose of resistance, thinking that it was meaningless, believing that he had not achieved anything, that he and his wife would die in a horrendous way for a hopeless cause, the composer replies harshly: ‘But how can you say that! Would you rather live for an unjust cause then die for a just one? There is no choice. Because we are who we are, this is the path we have to take.’

This is remarkable! Based on experiences in the war, psychological experiments – and, let’s be honest: our own experiences – we conclude that, because we are who we are, we don’t have a choice and therefore: fit in, conform, obey, go along and don’t resist.

But the composer who joined the resistance used the exact same arguments to come to the opposite conclusion: because we are who we are, we don’t have a choice, we have to resist. ‘So that we remain decent, just, loving people!’ as he maintained to Otto.

Ottochen’s parents had to pay with their lives for resisting Hitler and this captivating story appears to end with murder. But then Hans Fallada adds the words: “But we don’t want to end this book with their deaths. It is dedicated to life, unconquered life, life that still always triumphs over evil and tears, over misery and death.’

In his gripping novel Alone in Berlin, Hans Fallada tells the true story of two simple-hearted people from the German working classes, who decide to resist Hitler’s regime.

Otto and Anna Quangeln are true supporters of the Führer, until their only child is killed at the frontline in 1940. The condolence letter proclaims that their son died a ‘hero’s death for his Führer and his people’ – but Otto and Anna know this is a lie. The boy did not want to fight, he was against war. The parents are convinced that Hitler murdered their only child and decide to join the resistance. They don’t just want to resist the Führer, but also a society in which you can no longer think for yourself and always have to do what you are told. They decide to distribute cards all over Berlin. The first card shows: ‘Mother, the Führer has murdered my son.’ They aim to set their fellow citizens thinking. They hope that their peers will overcome their fears and become aware that Hitler’s regime is murderous, even that those who do not resist are accessories to the criminal regime.

But, it turns out that people are afraid and hand in the cards to the Gestapo. Eventually, the parents are arrested and know they won’t survive the trial. In prison, Otto is put in a cell with Dr. Reinhardt, a conductor who was courageous enough to warn people against the regime. Otto, an ordinary craftsman, regards the conductor with much scepticism and says: ‘Being a composer, what’s the point? I’m a cabinet maker, my work lasts for a hundred years. But music, well, when it stops there’s nothing left of your work.’ The composer replies: ‘And yet there is, my good fellow. The happiness inside that people experience when they hear good music remains.’

At a certain point a petty thief joins them in the cell and the dirty little rat steals their bread. When the composer responds to this with leniency, Otto gets angry: ‘You are too weak. We have to put this scumbag back in his place.’ But the composer replies: ‘Should we become just like the others then? They think that they can change our minds by hitting us. But we don’t believe in the supremacy of violence. We believe in goodness, in love, in justice.’

When Otto begins to doubt the purpose of resistance, thinking that it was meaningless, believing that he had not achieved anything, that he and his wife would die in a horrendous way for a hopeless cause, the composer replies harshly: ‘But how can you say that! Would you rather live for an unjust cause then die for a just one? There is no choice. Because we are who we are, this is the path we have to take.’

This is remarkable! Based on experiences in the war, psychological experiments – and, let’s be honest: our own experiences – we conclude that, because we are who we are, we don’t have a choice and therefore: fit in, conform, obey, go along and don’t resist.

But the composer who joined the resistance used the exact same arguments to come to the opposite conclusion: because we are who we are, we don’t have a choice, we have to resist. ‘So that we remain decent, just, loving people!’ as he maintained to Otto.

Ottochen’s parents had to pay with their lives for resisting Hitler and this captivating story appears to end with murder. But then Hans Fallada adds the words: “But we don’t want to end this book with their deaths. It is dedicated to life, unconquered life, life that still always triumphs over evil and tears, over misery and death.’